#11

The French far right's feminist takeover, plus a note on Le Pen

Sans Merci. The Baffler, April 2025.

It took Éric less than half an hour to bring up to women’s rights. It was March 2018—Éric was leading the Paris branch of the far-right National Rally’s youth wing and I was just beginning to report on France’s young far-right activists as part of my graduate school thesis,1 after first covering them during the country’s 2017 presidential election. We’d met at a café in Paris’s humble thirteenth arrondissement, a quiet corner of the left bank near the city’s southern border. We discussed his journey from a left-wing teenager in the New Anticapitalist Party to, at 21, a prominent part of France’s ascendant far right.

The party’s support in rural areas was growing, but it remained widely villainized in Paris, so I asked him about the challenges of campaigning in the capital city. He listed off the party’s most salient issues in Paris. “Security, women’s rights, sexual harassment, and democracy,” he told me, going on to elaborate on how unsafe some parts of the city had grown. He cited the specific street on which a friend of mine lived, and where I happened to be staying during that trip—a perfectly safe street in the center of the city, near the Gare du Nord train station and home to many immigrant-owned businesses where men of color often gathered on the sidewalk.

That conversation marked the first of many mentions of women’s rights and street harassment that I’ve heard over the past eight years reporting on the French far right. In my interviews with young National Rally activists from Paris to Marseille—as well as in countless statements from longtime party leader Marine Le Pen and other party officials—the far right has increasingly sought to frame its nationalism as a defense of women’s rights and liberal values. Immigrants, they insist, have come to France to catcall you in the street, to harass you on the metro, to force a veil over your head.

This rhetoric reached a new fever pitch last September, when 19-year-old Philippine Le Noir de Carlan’s body was found buried in Paris’s hulking Bois de Boulogne park, just behind her university. The suspect was a Moroccan immigrant who’d previously been convicted of rape. The far-right group Collectif Némésis, which calls itself “feminist and identitarian,” quickly mobilized around Philippine’s death, attracting attention in the French media and online.

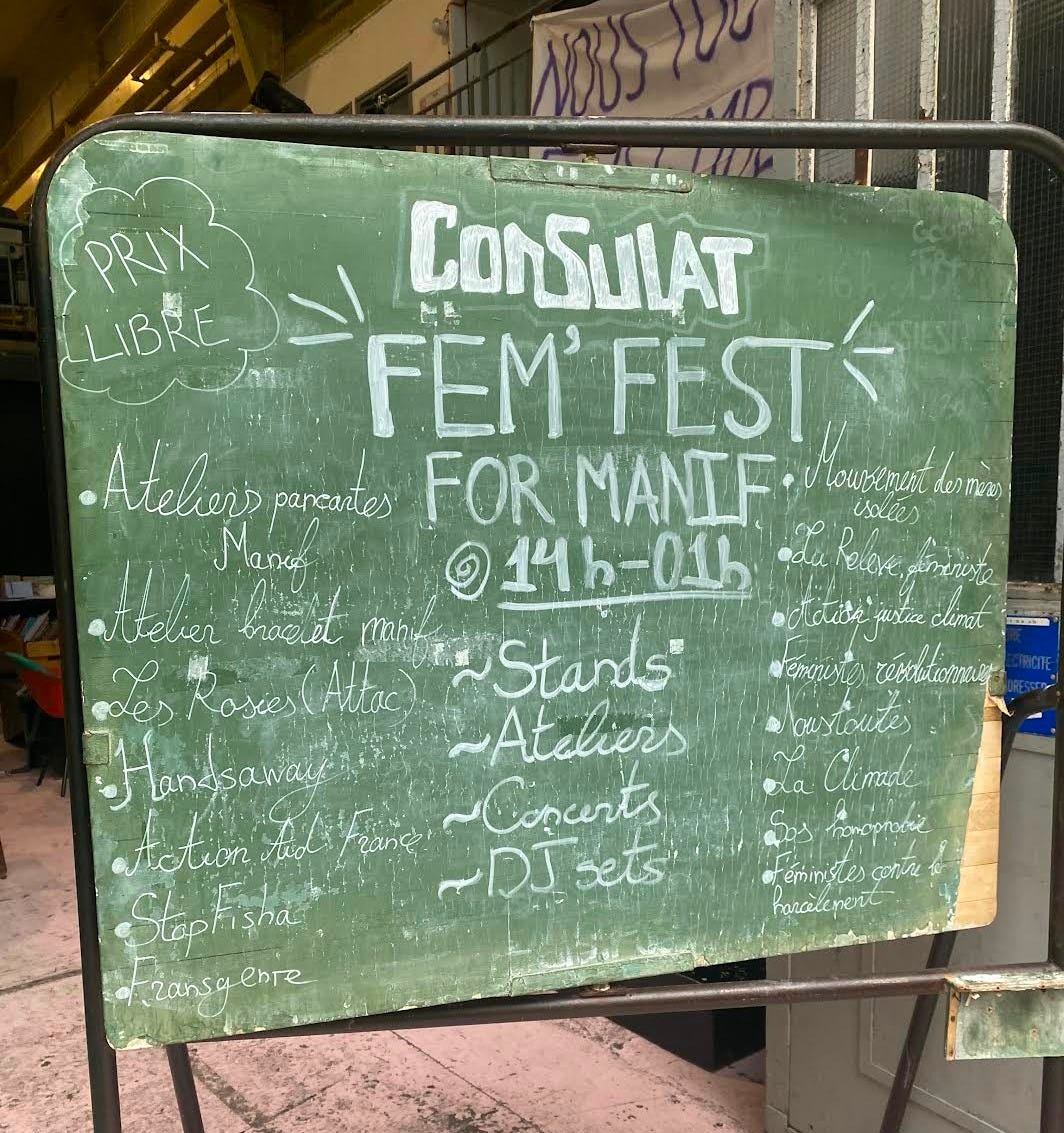

By the time I arrived in France a few weeks later, I’d spent nearly a decade thinking about femonationalism, the term sociologist Sara R. Farris coined to describe this phenomenon of the far right co-opting the language of women’s rights to bolster its case for nationalism and authoritarianism. My reporting on this story used Philippine’s death as a starting point to explore how femonationalism is playing out in France, how feminist groups are pushing back against it, and alternative approaches to combating street harassment. It put me in conversation with everyone from a Némésis activist to an antifascist organizer to a prison abolitionist, taking me all around Paris and eastward to Strasbourg, with a pit stop in Dijon and a run across the Rhine River from France to Germany. It also pulled me back to that 2018 conversation with Éric, helping me trace the long evolution of femonationalism that primed the far right to weaponize Philippine’s death so quickly and effectively.

The product of that reporting and research is my latest feature, appearing in the April issue of The Baffler magazine. You can find it online at the link below, but I recommend buying a physical copy if you have $14 to spare!

Sans Merci. The Baffler, April 2025.

As always, you can find the full archive of past newsletters here.

That reporting was published by Vice in 2020 and won an honorable mention in the 2021 Annual Writing Awards of the American Society of Journalists and Authors. It feels newly relevant in the wake of yesterday’s verdict finding Marine Le Pen guilty of embezzlement, rendering her ineligible to run for public office for five years and taking her out of contention for France’s next presidential election in 2027. This is a major setback for the National Rally. And yet, in some ways, the party has been preparing for this possibility for years. By growing its youth wing and elevating its ambitious young leaders—particularly 29-year-old party president and Le Pen protégé Jordan Bardella—to national prominence, the National Rally already has a viable candidate to take Le Pen’s place on the 2027 ballot.